- Why Buy Flood Insurance?

- Basics of the National Flood Insurance Program

- Recent Changes to Flood Insurance

- Flood Zones: Finding and Understanding Flood Insurance Rate Maps

- Flood Insurance Costs, Premium Setting, and Ways to Reduce Premiums

- Pre-FIRM vs. Post-FIRM Structures

- An Introduction to the Community Rating System and Sea-Level Rise

- Select Background on the National Flood Insurance Program

- Selected Terms and Definitions from FEMA’s Website for the National Flood Insurance Program

Written by: Thomas Ruppert, Florida Sea Grant Coastal Planning Specialist

Everyone lives in a flood zone.

What this oft-repeated observation means is that though the likelihood of a flood varies from property to property, almost no property is guaranteed to be safe from flooding.

Properties located in Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs) are at a greater risk of flooding than properties outside SFHAs. These properties have about a 25% chance of flooding during the term of a 30-year mortgage. (Special Flood Hazard Areas, often called “flood zones,” have a 1% annual chance of flooding during a storm.).

Properties located outside of SFHAs flood, too. In fact, it is estimated that between 66% and 80% of flood losses occur outside of SFHAs, and the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) notes that almost 20% of its payouts are to properties outside of SFHAs. Thus, even properties outside a SFHA can benefit from flood insurance, especially since NFIP coverage costs less outside of SFHAs.

For example, as of October 2014, a residential house without a basement can get $250,000 building coverage and $100,000 contents coverage for an annual policy premium of $414. The NFIP also has a “flood facts” page at the following link: Flood Facts.

A second reason to purchase flood insurance is because it may be illegal not to. Federal law requires flood insurance for all properties in SFHAs with federally backed mortgages. Because most mortgages are federally backed (95%, through Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or the Federal Housing Administration), practically everyone with a mortgage on a property in a SFHA must purchase flood insurance.

If you are required to have flood insurance and do not purchase it yourself, your lender will purchase it for you and charge you. If your lender does not ensure that you have flood insurance when required, the lender may have to pay large federal fines.

But do not wait until a storm is approaching to purchase flood insurance—the NFIP imposes a 30-day waiting period before flood insurance is effective to avoid this type of behavior.

Why is insurance coverage required by law?

Briefly, after a massive flood on the Mississippi River in 1927, many insurance companies went bankrupt. After this, most private insurance companies stopped offering flood insurance.

This left the federal government paying out millions of dollars in disaster payments every time there was a flood disaster because there was no insurance available to help property owners. Thus, the federal government decided it would be better to develop its own flood insurance program, collect premiums, and assess risk rather than just continually paying out for flood disasters without charging those most at-risk property owners.

For more detailed background and history, see the section: Select Background and History on the National Flood Insurance Program at the end of this publication.

A third reason to purchase flood insurance is because your homeowners’ insurance policy likely does not cover flood damage. Almost all property insurance policies specifically exclude flood damages from coverage. Usually only flood insurance covers flood damages.

The final reason to buy flood insurance is because you may not qualify for post-disaster federal aid. Many people assume that if they suffer losses from a flood, they will get federal assistance. However, for disaster grant funds to be made available, the President must first declare a federal disaster, which does not happen in all floods.

Even if a federal disaster is declared, if you are located in a flood zone and did not have flood insurance coverage, you can only receive federal aid for damages that exceed the limits of a policy from the NFIP. This means that you would only begin to receive assistance for flood damages once your losses exceed $250,000 for a structure and $100,000 for contents. Some disaster aid may still be available to you, but it will more likely be in the form of loans that must be paid back.

After changes to the NFIP in 2012 began dramatically raising premiums, the private flood insurance market began to awaken to the possibility that it could supply flood insurance for less than the NFIP.

As long as private flood insurance coverage is identical to or greater than NFIP coverage, it fulfills federal requirements for flood insurance. In Florida, one of the first to offer private flood insurance was The Flood Insurance Agency (mention of this private company does not constitute endorsement). After several months of offering policies cheaper than the NFIP’s for identical coverage in some instances, The Flood Insurance Agency stopped offering new flood policies in some areas as a way to control its exposure to risk.

It remains possible that as The Flood Insurance Agency spreads its risk by adding new policyholders in other states, it may again begin offering policies in more of Florida. It is also possible that additional private insurers will enter the flood insurance market. Changes to flood insurance in 2014 (see Recent Changes to Flood Insurance) have slowed the rise of insurance premiums for some policyholders, however, and this may mean that the private flood insurance market will now be slower to develop.

It might only begin expanding again once NFIP rates have had a few years to increase to rates that private insurers are willing to beat.

Congress established the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) in 1968. The NFIP is administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The NFIP provides federally backed flood insurance to property owners in participating communities.

The federal government became an insurer of flood losses through the NFIP because the private market stopped offering flood insurance. If your community does not participate in the NFIP, you cannot purchase flood insurance through the NFIP. You can determine whether your community participates in the NFIP by checking with your local floodplain administrator or by looking on this site: NFIP Community Status Book.

To participate in the NFIP, a community agrees to establish and enforce minimum regulations designed to help prevent and minimize flood damage. Examples of these regulations include limitations on development in floodways and floodplains, and requiring that new buildings constructed in floodplains be elevated above the established “Base Flood Elevation.” As part of the NFIP, FEMA created “Flood Insurance Rate Maps” (FIRMs).

These maps show the estimated area of flooding that may occur in a community due to a rain event that has a 1% chance of occurring in any given year, or the so-called 100-year storm. Again, those areas with a 1% annual chance of flooding are known as Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs) and are sometimes referred to as “flood zones.”

However, FEMA recognizes several different types of flood zones. If your property is located in a SFHA, you will need to purchase flood insurance from the NFIP, or equivalent insurance from a private insurer, if available, to qualify for a federally backed mortgage. Because most mortgage lenders are federally backed, property purchasers who seek to finance property in a SFHA should anticipate paying for flood insurance.

To determine whether your property is in a flood zone, visit www.floodsmart.gov and enter the property address into the “How Can I Get Covered?” sidebar. You can also find this information by navigating directly to the FEMA Flood Map Service Center, or, in many areas, by visiting your local government’s website and looking for resources related to flooding.

The NFIP sets policy premiums for each property based on the attributes of that property, including when the property was constructed, whether and how many times it has flooded in the past, whether it is in a SFHA, and the elevation of any buildings relative to the estimated level of flood waters for the area. Even if you own a property that is not in a SFHA, it is a good idea to purchase flood insurance.

Most flood losses occur outside of SFHAs, and almost 20% of NFIP payouts and large amounts of flood disaster aid go to properties that are outside of SFHAs. More information on flood insurance and the National Flood Insurance Program is available on Florida Sea Grant’s Coastal Planning page.

Homeowner frequently asked questions, or FAQs, are available from the Federal Emergency Management Agency at this link: Homeowner FAQ.

Major changes to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) occurred in 2012 and 2014. In 2012, a law known as the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act eliminated existing insurance premium subsidies for many policyholders in Special Flood Hazard Areas.

These were pre-FIRM policies that covered buildings constructed or substantially improved on or before December 31, 1974, or before the effective date of the community’s initial Flood Insurance Rate Map, whichever was later. The law’s elimination of subsidies led to increases in policy premiums that for some properties were quite large.

Due to input from affected policyholders, interest groups, and local governments, Congress revisited the law and in March of 2014 passed the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act. The new law modified some of the premium rate changes, but many parts of the 2012 law still remain in effect.

Under the new law, the costs of flood insurance will continue to climb for most policyholders. While the 2014 law was seen as giving relief to purchasers and sellers of property that otherwise would have been subjected to immediate and large premium increases, the change would have resulted in lower revenue for the overall federal flood program, a program already $20 billion in debt. Thus, the purpose of the 2012 law to address the NFIP’s deficit still needed to be considered.

The 2014 law still generates increased revenue for the NFIP, but it does it differently. First, while almost no pre-FIRM policies go up to the full-risk rate immediately, all pre-FIRM properties—not just properties that had been sold since the law took effect—did immediately begin the process of increasing to the full-risk rate. The changes also mandate that premiums for businesses may increase 25% per year while non-businesses may only increase a maximum of 18% per year.

Since the NFIP did not formerly collect information that allowed it to distinguish between businesses and non-businesses, it has now begun to do so at renewal. One of the key changes of the 2014 law is that it stopped most pre-FIRM properties from immediately losing all subsidies due to sale of the property or lapse of NFIP coverage. Now, such properties will be subject to a maximum possible yearly premium increase of 18%.

In addition, the law reinstated the policy of “grandfathering” properties. “Grandfathering” occurs when a property built at or above the base flood elevation of the then-current Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) is below a new BFE established in an updated FIRM. Under the 2014 revision, such properties will be allowed to use either the original FIRM in effect when the structure was built or the current FIRM, whichever results in a lower flood insurance premium.

Properties that are business or investment properties (such as rental properties); that are not primary residences (that is, lived in by owner over 50% of the year); or that qualify as “Severe Repetitive Loss” properties; will see a phase-out of subsidies. Premiums on these properties will increase up to 25% per year until their premiums reach the “real-risk rates” based on likelihood of flooding established by FEMA. To more fully understand the effect of the law revisions if you have a pre-FIRM structure, you may use this flow chart.

Property owners may find that costs for flood insurance have also risen because some fees have been added to raise additional revenue. Fees vary dramatically from property to property based on the type of policy and the use of the insured structure. For all policies there is now a surcharge that will remain in effect until all subsidized rates have been transitioned to full-risk costs.

The surcharge is $25 per year for primary residences and $250 per year for all others. There is now a policy service fee of either $44 for policies in a SFHA or $22 for Preferred Risk Policies (those outside of SFHAs). Finally, there is an assessment to fund a reserve from which the NFIP can draw to pay claims. This fee costs Preferred Risk Policies 10% of their premium and other policies 15% of their premium. You can find the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) summary of the 2014 law at this link: FEMA 2014 Summary.

Many factors determine how the recent flood insurance changes affect flood insurance policyholders. In the short term, some policyholders will pay more, and others will pay less. In the long run, premiums and costs will continue to increase for all policyholders as part of the effort of the NFIP to charge full-risk rates that cover the program’s exposure to flood losses.

For those wanting additional detail or more extensive materials on changes to the NFIP, you may see additional material from the FEMA’s website: Flood insurance reform.

A Flood Insurance Rate Map, also known as a “FIRM,” is a map that provides extensive information about potential flooding.

For most property owners, the most important part of the map is the so-called 100-year floodplain, also known as the “Special Flood Hazard Area” (SFHA). A property in such an area has a better than 1 in 4 chance of flooding during a 30-year mortgage. Note, however, two important points about the 100-year floodplain. First, “100-year” does not mean that an area will flood only once every 100 years. It refers to the statistical probability that an area has a 1% chance of flooding in any given year. History tells us that storms do not follow a schedule, so in fact, a 100-year floodplain could flood several times in a single year, or it might not flood for more than 100 years.

Second, building to the 1% annual probability storm is not a safety standard that will always prevent harm. During development of the NFIP, many people argued for a far more protective standard, the 500-year storm event, which calculates to a 0.2% annual probability of flooding. The stricter standard would protect more people, but it was eventually rejected because building to this standard would have included far more properties—and thus more expense to more property owners—and it was therefore not considered politically feasible.

Other locations in the world are far stricter. In the Netherlands, which is famous for its flood-control efforts, planning for flood control infrastructure requires meeting a standard for a 1 in 10,000-year storm event.

Depending on your local government’s involvement with the NFIP, the best way to find out if you are in flood zone may be to contact your local government’s floodplain manager to inquire. If that does not work, you may also visit www.floodsmart.gov and put your information into the “How Can I Get Covered?” sidebar, by navigating directly to the FEMA Flood Map Service Center.SFHAs are shown on FIRMs as a “Zone A” or “Zone V.” These may be accompanied by letter or a number after the letter A or Z. In Zone AE and VE, “Base Flood Elevation” has been calculated and will usually appear in parentheses under the zone. The “(EL ___)” represents the expected water elevation of a 1%annual chance flood.

No Base Flood Elevation has been determined in zones labeled only “A” or “A[+number].” In Zone A, the focus is on the water elevation, whereas in Zone V, it is not only the elevation that is important but also the movement of the water and waves because moving water can cause immediate structural failure, representing an additional hazard to that of rising waters. Thus, in a Zone V, the type of construction of the structure and not just its elevation is important. Zone V usually occurs very close to the coast or along large bodies of water.

Areas not in an SFHA are moderate- and low-risk flood areas. Moderate-risk zones are listed as Zone B and Zone X (shaded) and represent the area between the SFHA and the 500-year flood event. Zone C and Zone X (unshaded) are low-risk areas for flooding. In Zone D, the flood risk has not been analyzed. The NFIP offers a tutorial on how to read a flood insurance rate map: How to read a FIRM.

If you have determined that you must purchase flood insurance, or if you wish to purchase it voluntarily, you are probably wondering how much it will cost.

The calculation of flood insurance premiums is complex and depends on many factors, but two of the most important are the elevation of the structure relative to the Base Flood Elevation of the flood zone and the date the structure was built. Other factors that may impact the cost are the location of the structure, the type of construction, and the use of the structure.

Although calculating the correct premium for a specific property is quite complex, some general NFIP estimates for premiums for residential properties located outside of the SFHA are available at the following link: Choose your policy.

No estimates are available from the NFIP for properties located in SFHAs due to the number of factors affecting the rates and complexity of determining the correct premium. Indeed, it is possible to find, for example, two similar houses on the same block where one owner pays $400 per year for flood insurance whereas the other owner might pay a sum seven or eight times higher.

What might explain such a discrepancy?

It may be that the house with the more expensive premium is at the edge of a Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA) and the owner selected the maximum available coverage for contents and structure. However, the house with the lower premium might not be in a SFHA, and might have only $150,000 of coverage on the structure and no coverage on the contents. The amount of the difference based on location may seem unfair, but lines on a map can lead to such scenarios. Also, small details can have major ramifications.

For example, if any portion of a structure touches any part of a SFHA, the entire building is treated as being located in the SFHA. FEMA uses a rating guide book for policies. However, some structures need to go through a separate process called “submit for rate” because of their high-risk or unusual nature. A guidebook for the “submit-for-rate” process is available at the following link: Submit-for-rate Guidebook, but application of the standards is very complex, and only authorized agents are permitted to prepare quotes for submission to FEMA.

The best and easiest way to find out how much flood insurance costs is to contact an insurance agent. An insurance agent may provide you with a quote from FEMA or may look into private market flood insurance, which may offer comparable coverage for a lower premium (See, e.g., http://www.privatemarketflood.com/ [inclusion of this link does not constitute endorsement of “Private Market Flood”]).

Property owners considering private flood insurance should ensure that the flood insurance they are purchasing satisfies any mandated flood insurance and is acceptable to the mortgage holder before purchasing. A list of insurance agents through whom you can buy NFIP coverage or obtain a quote is located at the following link: Insurance Agent Locator.

For those wanting a more detailed explanation of how an NFIP policy premium is determined, a useful place to begin is Section V of Chapter 5, Rating Section, of FEMA’s Flood Insurance Manual (rev. April 2015).

If you believe your premium is not calculated correctly, you might want to get a second opinion from another insurance agent. If you are still unconvinced your premium is correct and you are brave, you may want to try to estimate your premium yourself, but bear in mind that this calculation is not for the faint of heart: you will need an excellent understanding of the workings and terminology of the NFIP, an “elevation certificate” for your property, the year your structure was built, and then the time and patience for working through the “Flood Insurance Manual” as you try to identify the correct premium rate.

You might also want to investigate whether you can take steps to reduce your premium. For example, the 2014 changes to the NFIP include an allowance for higher deductibles that can dramatically reduce premiums. A $10,000 deductible, for example, might reduce a $1,000 premium by as much as 40%. However, exercise caution. Although the NFIP is allowed to accept deductibles up to $10,000, if you have a mortgage on your property, the lender has the right to determine what deductible it will accept. Some lenders, depending on the insured property owner’s assets and other factors, may not be willing to allow high deductibles.

The most effective way to decrease NFIP premiums significantly is to reduce the risk of flooding by elevating a structure or relocating it to an area of one's property outside the floodplain. The NFIP provides much lower rates for structures that are above the “base flood elevation” on flood insurance rate maps.

Some kinds of remodeling might also reduce rates, such as raising utility equipment (i.e. air conditioners or furnaces), backfilling below-grade crawlspaces and basements, and installing proper flood openings and vents. Even if it is possible to elevate, relocate, or remodel a structure, one needs to calculate whether the premium savings are sufficient to justify the expense of these kinds of changes to a structure.

The date of construction of a structure can dramatically impact the cost of flood insurance. The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) distinguishes between pre-Flood-Insurance-Rate-Map (pre-FIRM) and post-FIRM buildings.

The definition given by the NFIP is: Pre-FIRM building: For insurance rating purposes, a pre-FIRM building is one that was constructed or substantially improved on or before December 31, 1974, or before the effective date of the initial Flood Insurance Rate Map of the community, whichever is later.

Most pre-FIRM buildings were constructed without taking the flood hazard into account. Thus, a post-FIRM structure is one that was built or substantially improved after the later of either December 31, 1974 or the adoption of the initial FIRM for your community.

What was a pre-FIRM building may effectively become a post-FIRM building required to come into compliance with current floodplain management standards if the building is substantially improved or substantially damaged.

Why the distinction between pre- and post-FIRM buildings?

Since its inception, the premiums for many policies in the NFIP have not been based on a calculation of flood risk. Rather, many policies were subsidized, in part out of political necessity. If pre-existing development that was built in floodplains before the first NFIP Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) had not been offered lower, subsidized rates, the program would not have garnered sufficient political support to pass Congress.

Congress hoped that temporarily offering subsidies would encourage more property owners to purchase flood insurance, and predicted that eventually subsidized properties would be replaced by newer, more flood-resistant structures. That has not happened nearly as quickly as predicted.

The large difference in treatment between pre-FIRM and post-FIRM structures is changing due to the 2014 changes to the NFIP. As premiums rise for pre-FIRM structures under the new law, property owners would be wise to get Elevation Certificates so that the full-risk premium can be calculated even if the property will maintain some level of subsidy, potentially for many years.

Having the Elevation Certificate will ensure that the NFIP can correctly calculate the eventual rate and not exceed it as rate increases are implemented. The recent changes to the NFIP are part of moving the NFIP towards a system in which the likelihood of flooding of a property is appropriately reflected in the cost of flood insurance rather than having subsidies for some structures just because they were built so many years ago.

All subsidies to pre-FIRM structures are now being slowly phased out. Thus, over the long term, rates may go up significantly for some pre-FIRM structures. One way to ascertain how much is to secure an elevation certificate and request a quote for the property once all subsidies have been removed. In addition, recent changes to federal law require that FEMA calculate what the rate for a property would be without a subsidy, and include this information on all future flood insurance bills.

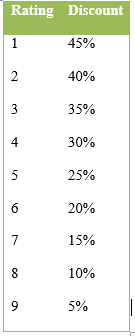

The CRS rates a community according to its implementation of strategies that reduce flood losses, such as preserving floodplains in their natural state or effectively maintaining stormwater systems. The more preventative the strategies, the more points a community earns in the CRS.

These points then translate into an overall rating between 1 and 9, with one being the best or highest rating and 9 the lowest. Each step up results in a 5% decrease in flood premiums for every NFIP policy in the community. For a more complete overview of the CRS program, see this FEMA website: Community Rating System. Information for local officials interested in the CRS is available through a CRS guide for local officials.

If they enter the CRS, most communities in Florida, by complying with existing state laws, should be able to qualify for at least a rating of 9 in the CRS and secure a 5% discount for all policyholders. The newest CRS “Coordinator’s Manual,” available at www.crsresources.org, was published in 2017 and includes numerous changes to previous editions.

These changes sought to adjust points to more accurately reflect the research that demonstrates which types of activities have the most value in preventing flood damages. The CRS program provides many different options for actions communities can take to decrease their flood risk and earn points towards a better CRS rating. For more information on the changes to the 2017, please see this FEMA list of changes from the 2013 CRS Coordinator’s Manual.

Because many communities in Florida have begun to examine their vulnerability to rising sea levels, the most recent coordinator’s manual includes several recommended actions specifically related to sea-level rise. Though the 2010 version of the Coordinator’s Manual did not mention sea-level rise, the 2013 version contains specific references to sea-level rise and/or climate change in five different actions communities can take to earn points toward a better CRS rating.

Communities can receive credits for:

- Showing climate change, sea-level rise, or other hazards not shown on Flood Insurance Rate Maps (CRS Manual, sec. 322.c);

- Disclosing to prospective purchasers the potential for flooding due to climate change or sea-level rise (sec. 342.d);

- Basing a regulatory map on future hydrological conditions, including sea-level rise (sec. 412.d);

- Including modeled changes to precipitation patterns due to climate change in watershed/drainage master plans (sec. 452.b); and

- Conducting flood-hazard assessment that incorporates climate change or sea-level rise (sec. 512.a, steps 4 and 5).

Flooding has always affected rivers; the impact on people has varied depending on where and how they live. During the flood of 1927, the Mississippi River reached 50 to 100 miles wide as it spilled over levees, forming a “chocolate sea” that stretched from Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico and flooding over 1,000 miles, leaving 700,000 people homeless and damaging or destroying137,000 buildings.

Then, as now, flooding resulted in major federal expenditures for disaster relief. Over the next eight decades, the pattern—catastrophic flooding leading to devastation and extensive property loss somewhere in the United States—was repeated over and over, despite billions of dollars of federal expenditures on flood control measures.

Even as the federal government increased its role and investment in flood protection, flood damages continued to increase because more and more people and development continued to move into floodplains. In 1891, W.J. McGee wrote in “The Floodplains of Rivers” that “as population has increased, men have not only failed to devise means for suppressing or escaping this evil [flood], but have with singular short-sightedness, rushed into its chosen paths.”

In fact, some observed that federal flood control measures encouraged development in areas subject to flooding because if a flood problem developed, certainly the federal government would have to build something to decrease the flood risk. To battle this counter-productive dynamic, a movement developed to promote land-use planning that discouraged development in floodplains.

One problem with this model was a lack of good information about flood risk. Thus, on a regional scale beginning in the 1950s and nationally in the 1960s, the federal government funded studies to delineate flood-hazard areas around the country. As flood risks grew, private insurers began dropping flood risk from their policies. Insurers realized that their payouts for flood loss were far higher than the premium income, and they lacked sufficient information to accurately price flood risk.

The flood insurance market was also subject to “adverse selection,” or the phenomenon whereby only those most likely to flood would buy the insurance, thus making it harder to lower premiums and make coverage affordable by effectively spreading the risk broadly. In response to continually increasing federal outlays for flooding disaster relief, the lack of a private insurance market offering flood coverage, and a desire to promote better development practices, Congress established the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) in 1968.

Communities were offered the option of participating in the program to make flood insurance affordable to their residents. In exchange, participating communities had to agree to minimum regulations for floodplain management, including limitations on development in floodplains. Through the NFIP, the federal government sought to protect taxpayers’ interests and put the risk and cost of development in floodplains back onto the local government and property owner by providing flood risk information through maps and insurance premiums.

Many argue that the NFIP failed in this mission and, in fact, encouraged further development in floodplains, but a comprehensive review of the literature on the NFIP failed to either clearly support or contradict this view (Evatt, Dixie Shipp, National Flood Insurance Program: Issues Assessment, A Report to the Federal Insurance Administration, 31 January 1999).

Because rates were not always set to reflect risk and because of the high cost of creating flood maps, for much of its history the NFIP has been supported by general taxpayer revenues. Starting in about 1985, the NFIP began mostly supporting itself , collecting premiums that were, on average, sufficient to pay for administration and claims. This 20-year successful era ended in 2005 with Hurricane Katrina. Katrina killed thousands of people and caused billions of dollars in damage, all of which cost the NFIP over $16 billion in payments, or more than eight times as much as it had ever paid out in a year.

The NFIP had not made much headway on making up an $18 billion debt when Superstorm Sandy ravaged the Northeast Atlantic coast. Sandy caused $37 billion of damages in New Jersey alone and about $7 billion in total NFIP-insured losses in the affected region. Again, the NFIP had to borrow money to pay these claims, so the NFIP is now about $26 billion in debt. A constant challenge for the NFIP has been the mapping of flood risk and delineation of floodplains.

The federal government has spent billions of dollars and mapped thousands of miles of floodways along streams and rivers. Nonetheless, mapping of floodplains is often fraught with technical challenges, especially when being done on such a large scale. It is not possible to make the maps perfect representations of what actually occurs in a flood, and the necessarily imperfect maps have regulatory and economic impact, which unsurprisingly has meant there have been many legal challenges to the Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMS) used by the NFIP.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is, like most insurance, complex. To help understand some of the basic terminology and acronyms you will encounter, here are some selected definitions. To find additional definitions, you may visit FEMA’s website for definitions at www.fema.gov/national-flood-insurance-program/definitions.

The BFE is the regulatory requirement for the elevation or floodproofing of structures. The relationship between the BFE and a structure's elevation determines the flood insurance premium.

In areas designated as Zone A, the community must obtain, review, and reasonably utilize BFE data available from a Federal, State, or other source and use these data as criteria for requiring that new construction and substantial improvements of residential structures have the lowest floor (including basement) elevated to or above the BFE.

All new construction and substantial improvement in Zones V1-30, VE, and also Zone V (if BFE data is available), must be elevated on pilings and columns so that the bottom of the lowest horizontal structural member of the lowest floor (excluding the pilings or columns) is elevated to or above the BFE.

For residential structures in AO Zones, the lowest floor (including basement) must be elevated at least as high as the depth number specified in feet on the community's map, or at least two feet if no number is specified.

Zone A: Areas subject to inundation by the 1-percent-annual-chance flood event generally determined using approximate methodologies. Because detailed hydraulic analyses have not been performed, no Base Flood Elevations (BFEs) or flood depths are shown. Mandatory flood insurance purchase requirements and floodplain management standards apply.

Zone AO: Areas subject to inundation by 1-percent-annual-chance shallow flooding (usually sheet flow on sloping terrain) where average depths are between one and three feet. Average flood depths derived from detailed hydraulic analyses are shown in this zone. Mandatory flood insurance purchase requirements and floodplain management standards apply. Some Zone AO have been designated in areas with high flood velocities such as alluvial fans and washes. Communities are encouraged to adopt more restrictive requirements for these areas.

Zone VE and V1-30: Areas subject to inundation by the 1-percent-annual-chance flood event with additional hazards due to storm-induced velocity wave action. Base Flood Elevations (BFEs) derived from detailed hydraulic analyses are shown. Mandatory flood insurance purchase requirements and floodplain management standards apply.

Thanks to the many individuals that provided review and comment on this publication. They include: Holly Abeels, Florida Sea Grant and UF/IFAS Extension Agent, Brevard County; Rebecca Burton, Communications Coordinator, Florida Sea Grant; Libby Carnahan, Florida Sea Grant and UF/IFAS Extension Agent, Pinellas County; Melissa Daigle, Legal Coordinator, Louisiana Sea Grant; Professor/Dean Emeritus Robert Jerry, UF Levin College of Law; Christine Klein, UF Levin College of Law; Charlene Luke, Professor, UF Levin College of Law; Shana Jones, Public Service Asst., Univ. of Georgia; Niki Pace, Senior Research Counsel, MS/AL Sea Grant Program; Kelly Spratt, Local Gov’t Outreach Coord., Univ. of Georgia; and Dorothy Zimmerman, Director of Communications, Florida Sea Grant. Of course any errors or omissions remain my own.