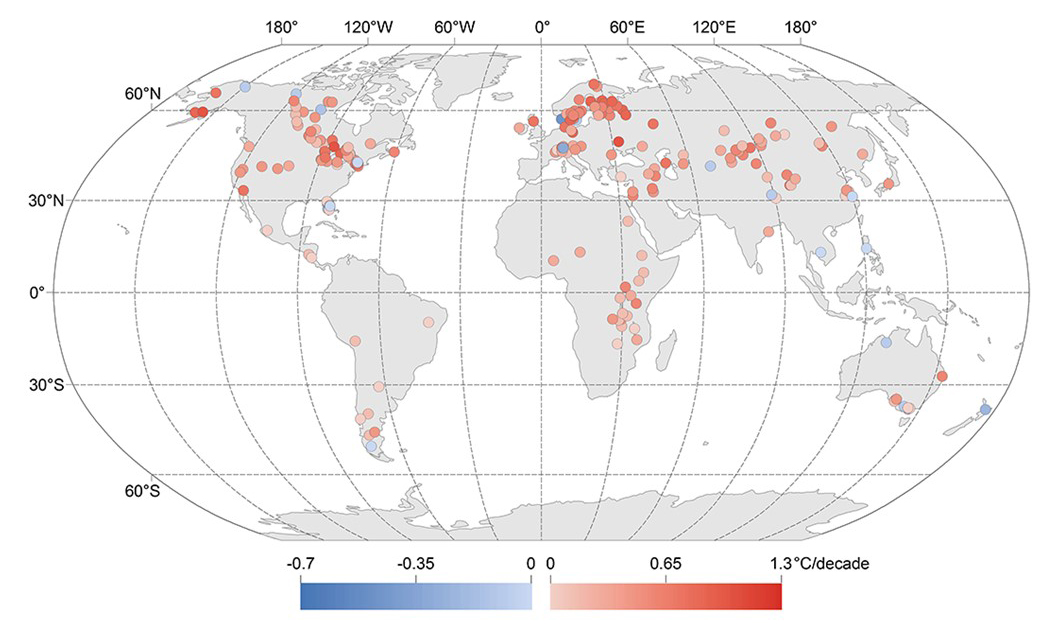

This map depicts trends in lake summer surface temperatures from 1985 to 2009. Most lakes are warming, and there is large spatial heterogeneity in lake trends. Note that the magnitudes of cooling and warming are not the same. (Figure courtesy Geophysical Research Letters)

Editor’s Note: This article is compiled from reports by Washington State University, Illinois State University, and UF/IFAS News.

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — Climate change is rapidly warming lakes around the world, threatening freshwater supplies and ecosystems, according to a new study spanning six continents.

More than 60 scientists took part in the research, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters and announced December 16 at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. The study authors include Karl Havens, director of Florida Sea Grant and a professor with the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

The full study, titled, “Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe,” is available free of charge at this link.

The study showed that lakes are warming an average of 0.6 degrees Fahrenheit each decade. That’s greater than the warming rate of either the oceans or the atmosphere, and it could have profound effects, scientists say.

At the current rate, algal blooms, which can ultimately rob water of oxygen, are projected to increase 20 percent in lakes over the next century. Algal blooms that are toxic to fish and other animals would increase by 5 percent. And these rates imply that emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas with 25 times the heat-trapping capacity of carbon dioxide, will increase 4 percent over the next decade.

“Lakes are critically important to people, because they are sources of drinking water, irrigation water and fisheries,” said Havens, an ecologist with the UF/IFAS School of Forest Resources and Conservation.

Temperature is one of the most fundamental and critical physical properties of water, Havens said. It controls a host of other properties that may in turn influence the life cycles of organisms that have evolved within strict environmental boundaries. When the water temperature in a lake swings quickly and widely from the norm, life forms in that lake may change dramatically and even disappear.

“These results suggest that large changes in our lakes are not only unavoidable, but are probably already happening,” said lead author Catherine O’Reilly, an associate professor of geology at Illinois State University. Earlier research by O’Reilly has linked declining productivity in lakes with rising temperatures. Many of the study authors, including O’Reilly and Havens, are members of the Global Lakes Temperature Collaboration, an international research consortium.

Funded in part by NASA and the National Science Foundation, the study is the largest of its kind and the first to use a combination of long-term hand measurements and temperature measurements made from satellites, offsetting the shortcomings of each method.

Study co-author Simon Hook, science division manager at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Cal., said satellite measurements provide a broad view of lake temperatures over the entire globe. But they only measure surface temperature, while hand measurements can detect water temperature at a variety of depths. Also, satellite measurements are only available from the past 30 years, whereas hand-measurement records for some lakes go back more than a century.

To produce the study, the authors analyzed data collected from 235 lakes that were monitored for at least 25 years. While that’s a fraction of the world’s lakes, the selected group represents more than half the world’s freshwater supply.

The researchers said various climate factors are associated with the warming trend. In northern climates lakes are losing their winter ice cover earlier, and many areas of the world have less cloud cover now than in the past, causing surface waters to receive more sunlight.

Many lake temperatures are rising faster than the average air temperatures, according to the study. Some of the greatest warming is seen at northern latitudes, where rates can average 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit per decade. Warm-water, tropical lakes have had lesser temperature increases, but future warming of these lakes could have large negative impacts on fish populations. This issue is a particular concern for the African Great Lakes, home to one-fourth of the planet’s freshwater supply and an important source of fish for food.

Havens said it’s important to keep in mind that the study findings show rising lake temperatures are an issue everywhere.

“The consensus among the researchers is that climate impacts should be considered whenever we assess the ecological health of lakes,” Havens said. “Increased water temperature may have cascading effects throughout a lake ecosystem and we need to understand this issue thoroughly before we can address it effectively.”

Additional Reading: Karl Havens as authored several articles relating to the effects of climate change on Florida’s aquatic ecosystems. They are available from EDIS, the Electronic Data Information Source of UF/IFAS Extension, at this link.

Contact:

Karl Havens, 352-392-5870, khavens@ufl.edu

Catherine O’Reilly, 309-438-3493, cmoreil@ilstu.edu

Simon Hook, 818-354-0974, Simon.J.Hook@jpl.nasa.gov