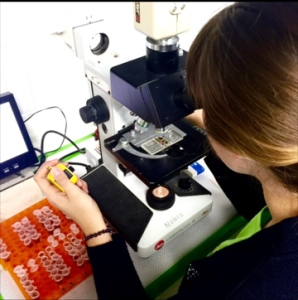

Toonder’s research analyzed how different strengths of sunscreen impact an oyster’s ability to filter feed.

When Madison Toonder was in 6th grade, she attended a week-long day camp at Busch Gardens where she learned about the filter-feeding power of oysters and how their populations are declining. Her curiosity sparked, she headed home to peruse the internet about a shellfish most known for its place on seafood menus, but ecologically important as well.

Today, the now 14-year-old is learning about the harmful effects that sunscreen chemicals leeching into coastal waters can have on oyster reefs, and proposing legislation to do something about it.

Toonder, who attends Ponta Vedra High School and Florida Virtual School, is writing a bill for the Florida legislature that proposes to cap the amount of active ingredients in sunscreen. Her efforts are based on the results of experiments she has conducted which show that certain sunblock ingredients, such as nano-sized zinc oxide, build up like plaque and inhibit an oyster’s ability to filter feed. In high percentages, the chemicals can kill some oysters outright.

Considering the number swimmers and sunbathers who lather on sunscreen at Florida’s coast each year, the problem could be significant.

Her results also showed that the SPF of the sunscreen, its sun protection factor, makes a difference.

“When you go from SPF 15 to SPF 70, a lot of things change,” Toonder said. “SPF 15 contains about 25 percent active ingredients, while SPF 70 contains about 50 percent active ingredients.”

Yet SPF 70 only provides about 5 percent more sun protection than SPF 15, Toonder said.

“It’s disproportional and it’s not as effective as you would hope. So there is an increase in chemicals entering your body and the environment, but you’re not getting a lot of protection increase,” she said.

Toonder attended the UF College of Law’s Public Interest Environmental Conference to meet other researchers and legal specialists who may be able to help draft her bill.

It’s important to note that results from one study cannot be taken as certainty, but Toonder is well on her way to bringing public awareness to a potential environmental problem. She is working actively to bring this bill to the public eye and has been working with experts along the way, including the Florida Sea Grant legal specialist, Tom Ankersen.

Toonder contacted Ankersen, a legal skills professor at the University of Florida Levin College of Law, for advice about how she should proceed with her proposal.

“I must admit I was a bit skeptical when Madison first contacted me, but once I had the opportunity to see the scientific work she had done and her eagerness to translate that into meaningful change through policy, I became convinced that she was something special,” Ankersen said.

Ankersen invited Toonder to his college’s annual Public Interest Environmental Conference where she was able to connect with other researchers and scientists for guidance. She said he’s agreed to be a mentor to her in the bill writing process.

Toonder, a 9th-grader who attends Florida Virtual School, hopes this experience will help her on her journey to become a marine veterinarian with a focus on conservation.

“Right now there is no overseeing committee for micronized chemical sunscreen. There’s no cap on the chemicals in the active ingredients,” Toonder said. “So it’s definitely great to have his help.”

Toonder is still in the beginning stages of drafting the bill. For reference, she has been researching previous bills such as the federal legislation signed into law in 2015 banning the use of products containing plastic microbeads. Ultimately, she said the whole process has been a learning experience for her.

“Environmental conservation is extremely important to me. I aspire to be an exotic or marine animal veterinarian with a focus on conservation so this is right up my alley,” Toonder said. “I love doing this, looking at the broad expanse of environmental protection and the different pollutants that harm it.”

Editor’s note: A discussion of sun protection factor (SPF) and how sunscreens work can be found at the web page Sun Safety from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.