By Karl Havens, Florida Sea Grant director

Editor’s note: When originally posted on July 6, 2018, this article stated that the algae bloom was on the surface of Lake Okeechobee. Based on field observations, the condition of the bloom appears to be changing over time. Sometimes the bloom is on the surface and other times it is in the water column just below the surface. It is impossible to tell the difference between a bloom on the surface and a bloom in the water column from satellite images alone. At this time, the lake is not being monitored regularly for algae blooms. This article continues to be updated as new information is available.

Summer is back in full force and so are the harmful algae blooms.

In early June, satellite imagery from the NOAA’s National Ocean Service indicated that a bloom of blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, was forming in Lake Okeechobee. The massive bloom had grown in size and as of July 2, was present in 90 percent of the open water area of the lake. The most recent image from July 6 suggests that the bloom has diminished. However, we do not know if this is the beginning of a downward trend or if it will come back again.

Reminiscent of summer 2016, the algae has also made unwelcome appearances in the St. Lucie River and Estuary on Florida’s east coast, and the Caloosahatchee River and Estuary on the west coast, posing a threat to humans and aquatic life. At the same time, reports of large blue-green blooms in states as far away as Kansas and Ohio have surfaced.

But, what is really causing these unsightly events?

Blue-green algae need a few specific ingredients and conditions to grow: nutrients, sunlight, carbon dioxide and relatively calm water.

Nutrients, in particular nitrogen and phosphorous, are critical to help build the algae’s cellular mass. In the watershed north of Lake Okeechobee, it is estimated that the soils and wetlands contain enough nutrients from past agricultural activities to fuel high nitrogen and phosphorus inputs into Lake Okeechobee for the next 50 years, even if farming stopped today.

Sunlight and carbon dioxide from the water help fuel photosynthesis. And relatively calm conditions prevent algae from mixing too deeply into the water and being robbed of sunlight. But, in places with very shallow waters, calm conditions are not as critical because algae mixed to the bottom may still have enough light to fuel growth.

Hurricane Irma, which pummeled a large portion of Florida’s peninsula in 2017, is partly to blame for this summer’s bloom. The storm brought heavy rainfall over the watersheds located north of the lake and around the two estuaries. Each of these three watersheds contain sources of high nitrogen and phosphorus levels from past and present agricultural activities and leaking septic systems. One heavy rainfall can flush these bloom-fueling nutrients into the lake and estuaries.

And, that’s exactly what happened. This rainfall, combined with extremely hot summer days and plenty of sunshine completed the recipe for today’s massive blooms. The heat wave lurking over much of the midwestern and eastern United States also explains the prevalence of blooms this summer in other nutrient-polluted lakes.

Water discharges by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from Lake Okeechobee are often blamed for blooms in the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee estuaries. The Corps discharges water from the lake when the water levels get too high and threaten the integrity of the Herbert Hoover Dike. Through a set of canals, these water discharges eventually end up in the rivers and estuaries to the east and west.

However, it is hard to pinpoint whether or not the lake discharges are the direct cause of the river and estuary blooms, because the watersheds around those rivers and estuaries also contain plenty of nutrients. Those watersheds also experienced heavy rainfall and nutrient runoff in some months before the blooms surfaced.

Interestingly, even during drought years, the Caloosahatchee River develops intense blue-green algae blooms, independent of discharges from Lake Okeechobee. The remedy is often a pulse of water from the lake to push the bloom out to sea where it dies because the algae cannot tolerate salt water. But this summer, some experts are concerned about that approach due to a large red tide in the Gulf of Mexico, just offshore of the Caloosahatchee Estuary.

If the freshwater blue-green bloom is pushed out to sea with a pulse of water, and the algae cells burst open since they cannot tolerate salt water, large amounts of nutrients could be released and may worsen the red tide.

How did we get to the place where weather controls algae blooms in our lakes?

It reflects decades of human intervention on the land – adding fertilizer, growing crops, raising cows and cattle, fertilizing lawns and installing septic tanks – around these once-pristine water bodies.

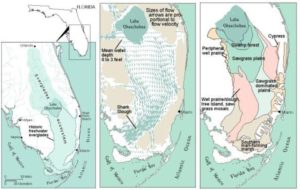

In 1900, Lake Okeechobee was at the center of a large inter-connected Everglades wetland (left). Water flowed into the lake from the northeast and exited to the west, south, and southeast, either through meandering creeks or as a broad sheet flow (center). The swamp forest of pond apple trees and much of the sawgrass plains at the southern end (right) have now been drained and converted to agriculture. Photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

Additionally, towns, cities and the Corps have installed a massive system of canals that act as a fast route for water from the land to the lake and the estuaries. Historically, rainfall slowly made its way to those waters through wetlands and meandering creeks that naturally filtered excess nutrients out of the water. Today, it quickly shoots downstream in straight drainage canals.

Much work has been done to reduce the amount of nutrients running off agricultural lands. The Corps and the South Florida Water Management District are currently working on projects to capture water after large storms and filter out legacy nutrients before the nutrients reach lakes and estuaries. These projects are decades from completion in most cases, and we will likely continue to see times of heavy rainfall followed by periods of sunshine and hot days, which will lead to more severe algae blooms on our lakes and estuaries.

Blue-green algae blooms are a worldwide problem in lakes heavily polluted with nutrients. Current research shows that if climate change causes further warming of lakes and estuaries, blooms will become more intense and more toxic. It will be easier to control blooms by curtailing nutrient inputs now than it will be in a warmer future.

Florida Sea Grant maintains this page on algae blooms in Florida, which can be bookmarked for future reference. Visit: https://archive.flseagrant.org/algae-blooms/.

Karl Havens has 35 years experience in aquatic research, education and outreach, and has worked with Florida aquatic ecosystems and the use of objective science in their management for the past 23 years. His area of research specialty is the response of aquatic ecosystems to natural and human-caused stressors, including hurricanes, drought, climate change, eutrophication, invasive species and toxic materials. He is a recipient of the Edward Deevey, Jr. Award from the Florida Lake Management Society for his research dealing with Florida lake ecosystems.