This section is an excellent resource for anglers interested in learning more about sharks and shark fishing in Florida. Please explore these new pages and media to learn more about shark biology and ecology, local shark science, best handling practices and recommended guidelines for catch-and-release fishing. The videos on this page were funded by Florida Sea Grant and produced by former Florida Sea Grant Scholar, Austin Gallagher, a research biologist and Ph.D. student at the University of Miami.

- Why Shark Catch and Release?

- Conservation of a Top Predator

- Florida's Shark Fisheries

- Shark on the Line!

- Species Focus

- Best Release Practices

Today many species of sharks are threatened due to overfishing. Sharks are slow-growing, give birth to relatively few young, and take many years to reach maturity. These factors make sharks vulnerable to overfishing, with recovery being difficult for some species.

Large apex predators such as hammerheads and sandbar sharks have declined by up to 90 percent in recent decades. Other species have decreased, but are slowly showing signs of stabilization.

Due to their position at the top of many food chains, sharks are ecologically important. In addition, shark species are economically important as a resource, particularly to recreational fishermen. These creatures fascinate us, and experiencing sharks in their natural habitat can be an incredibly exciting and memorable experience.

How did sharks become threatened?

Harvest for flesh and fins

Commercial landings of sharks in Florida rose from 287,531 pounds in 1980 to 7.3 million pounds in 1990 due to the growing acceptance of shark meat as seafood and the increase in prices in the Asian shark fin markets. The dramatic increase in landings caused some sharks to become overfished or threatened.

Recreational catch

Sharks are predators and are therefore present in locations where people fish, causing them to be caught unintentionally. Some species of sharks experience high stress levels when fighting on the line and may die shortly after being released.

Shark fishing in Florida has also become a recreational activity. Recreational fishing is a potential threat if the largest individuals from the population are removed and killed, as they have the greatest reproductive potential.

Fishermen who are not versed on successful catch-and-release practices may fight the sharks for too long, exposing them to a greater risk of mortality after release.

Biological challenges

Many sharks venture inshore to Florida’s waters to give birth, rendering them vulnerable to harvest during these times.

Sharks also grow and mature very slowly, meaning certain species, particularly the longer-living ones, cannot reproduce until their teens or later. Many species will produce fewer than 10 pups per brood and do not reproduce every year.

The combination of low reproductive rates, biological susceptibility to overfishing, and other specialized characteristics are what cause them to be threatened.

Sharks are one of the oldest groups of animals on our planet. There are more than 500 different species of these ancient fish. They come in various shapes and sizes. Sharks can be found in all types of ecosystems and water temperatures globally. Almost all sharks are predatory, meaning they hunt and consume other prey species. Many sharks are also top, or apex, predators in their respective habitats.

Sharks are one of the oldest groups of animals on our planet. There are more than 500 different species of these ancient fish. They come in various shapes and sizes. Sharks can be found in all types of ecosystems and water temperatures globally. Almost all sharks are predatory, meaning they hunt and consume other prey species. Many sharks are also top, or apex, predators in their respective habitats.

Today, sharks are a primary focus of conservation and research efforts worldwide, and Florida boasts a handful of groups dedicated to studying them. Florida is also recognized as a leader in shark fisheries management.

Responsible Angling

Catch-and-release fishing by recreational anglers plays a major part in conservation and allows these fishermen to still experience the thrill of catching a shark.

However, the sustainability of catch-and-release fishing relies upon the assumption that the released fishes will survive with minimal impacts to animal function or health. Research has shown that post-release survival rates in many species can be very high when the proper gear is used and fish are handled properly.

Additional Resources

- Shark Information (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Fish Handling Practices (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Common Sharks of Florida (Florida Sea Grant)

- A Guide to Circle Hooks (Florida Sea Grant)

- Recreational Shark Fishing Healthy Catch-and-Release (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Sustainable Sport Fishing for Thresher Sharks (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Podcast: Hooked on Sharks (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Best Practice Shark Handling Guide (The Shark Trust)

- A Guide to Sharks, Tunas & Billfishes in the U.S. Atlantic & Gulf of Mexico (Rhode Island Sea Grant)

- Shark Biology and Conservation (MOTE Marine Laboratory)

- Sharks: The Animal Answer Guide (Gene Helfman and George H. Burgess)

- Circle hooks and sharks (Bulletin of Marine Science)

- Guy Harvey Research Institute Shark Tracker

Photo by Austin Gallagher

Florida remains one of the best locations in North America to interact with many species of sharks. Anglers therefore have a responsibility to ensure they are conservation-minded in their fishing activities.

People have been interacting with sharks in Florida for decades. Interest in fishing for these predators dates back to before the 1900s. Interest increased during the 1950s to 1970s as anglers would commonly encounter sharks while targeting other species, or have their fish lost to sharks.

Photo by Austin Gallagher

From ‘Catch and Kill’ to Conservation

Anglers soon realized the thrill and excitement of hooking and catching sharks, which were more abundant at the time when compared to today. In the wake of the 1975 blockbuster movie “Jaws,” sharks were suddenly cast in a negative light and people were galvanized to seek and destroy sharks. At this point the primary mentality of recreational shark fishermen in Florida and the greater United States was to “catch and kill.”

Shark fishing tournaments increased in popularity and prevalence, with the greatest awards and honors bestowed on those who killed the largest sharks. This trend continued throughout the 1980s until the mid-1990s when a conservation ethic began spreading, which included a shift toward catch-and-release shark fishing.

Today sharks are recognized as a significantly valuable economic resource through catch-and-release recreational fishing in the state of Florida, where a shark is more valuable to catch again another day.

Charter boat captains offer shark fishing trips year-round in Florida. Several different species may be targeted, depending on the season and weather conditions.

Why sharks call Florida home

Populations of sharks in the state have historically been abundant due to the variety of marine habitats such as reefs, estuaries, mangroves, the open shelf and the over one-thousand miles of coastline across the state.

Populations of sharks in the state have historically been abundant due to the variety of marine habitats such as reefs, estuaries, mangroves, the open shelf and the over one-thousand miles of coastline across the state.

Sharks use these habitats throughout their lives for feeding, mating, pupping and migrating. The Atlantic coast boasts a wide variety of species that inhabit both in-shore and offshore systems. Migratory species using the Gulf Stream utilize the warmer waters off Florida for feeding. The Gulf of Mexico is an area of strong shark abundance, but certain species have suffered declines in both regions.

Additional resources

- Shark Information (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Fish Handling Practices (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Common Sharks of Florida (Florida Sea Grant)

- A Guide to Circle Hooks (Florida Sea Grant)

- Recreational Shark Fishing Healthy Catch-and-Release (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Sustainable Sport Fishing for Thresher Sharks (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Podcast: Hooked on Sharks (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Best Practice Shark Handling Guide (The Shark Trust)

- A Guide to Sharks, Tunas & Billfishes in the U.S. Atlantic & Gulf of Mexico (Rhode Island Sea Grant)

- Shark Biology and Conservation (MOTE Marine Laboratory)

- Sharks: The Animal Answer Guide (Gene Helfman and George H. Burgess)

- Circle hooks and sharks (Bulletin of Marine Science)

- Guy Harvey Research Institute Shark Tracker

What actually happens to a shark when it is hooked, fought and released?

- Hook is set into the shark, ideally in jaw, but can also get hooked in mouth, gills, stomach, or foul hooked in body, fins, or tail.

- Shark fights against fishing line, causing changes in their physiology. This is known as the “fight or flight” stress response.

- Certain species will fight harder than others.

- Shark is eventually brought to the side of the boat, dehooked and released.

Stress on Sharks

Fighting the shark on the line causes the greatest distress on the animal, which can result in increases of stress hormones and changes in blood chemistry.

These changes can cause the build up of metabolic products and acids that can cause death if the shark does not recover from the stress event or fights itself to extreme exhaustion. In some cases, sharks can recover from the fishing stress.

A recent study led by researchers at the University of Miami analyzed how five different species of sharks in Florida responded to the stressors of catch and release fishing.

Watch this short video for an explanation of what the researchers found!

The researchers looked at how blood physiology and reflexes changed in blacktip, bull, great hammerhead, lemon and tiger sharks. The animals were caught using a variety of fight times, ranging from two minutes to 180 minutes.

The team also placed satellite tags on bull, hammerhead, and tiger sharks to estimate their survival rates after release. The researchers documented a wide range of sensitivity to fishing between species.

Tiger and lemon sharks were shown to recover from catch-and-release fishing, while other sharks like hammerheads and blacktips were much more sensitive.

The study found that nearly 50 percent of hammerheads actually suffered mortality after they were released, regardless of the length of the fight.

Even though a shark may swim away after it is released, it does not mean that it will necessarily survive the encounter. This research was supported by Florida Sea Grant and it can be found at: University of Miami Researchers Study Shark Stress

Explore the Species Focus page to learn more about the results of the study and which species are more susceptible to stress.

In Review

Photo by Austin Gallagher

Research shows that different species of sharks seem to have their own personality in terms of how they respond to catch and release. Some species are great candidates for catch-and-release fishing, while others are clearly not. For those species which fall into the sensitive category, anglers are encouraged to be especially responsible and act in accordance with the recent scientific findings and the best handling practices available.

Additional Resources

- Shark Information(Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Fish Handling Practices(Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Common Sharks of Florida(Florida Sea Grant)

- A Guide to Circle Hooks(Florida Sea Grant)

- Recreational Shark Fishing Healthy Catch-and-Release(NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Sustainable Sport Fishing for Thresher Sharks(NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Podcast: Hooked on Sharks(NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Best Practice Shark Handling Guide(The Shark Trust)

- A Guide to Sharks, Tunas & Billfishes in the U.S. Atlantic & Gulf of Mexico(Rhode Island Sea Grant)

- Shark Biology and Conservation (MOTE Marine Laboratory)

- Sharks: The Animal Answer Guide(Gene Helfman and George H. Burgess)

- Circle hooks and sharks(Bulletin of Marine Science)

- Guy Harvey Research Institute Shark Tracker

Florida is home to more than 20 different species of sharks that are found in a variety of habitats, ranging from inlets to creeks and reefs, and in the open ocean. This page is designed to profile a handful of species that are commonly encountered by catch-and-release anglers.

Florida is home to more than 20 different species of sharks that are found in a variety of habitats, ranging from inlets to creeks and reefs, and in the open ocean. This page is designed to profile a handful of species that are commonly encountered by catch-and-release anglers.

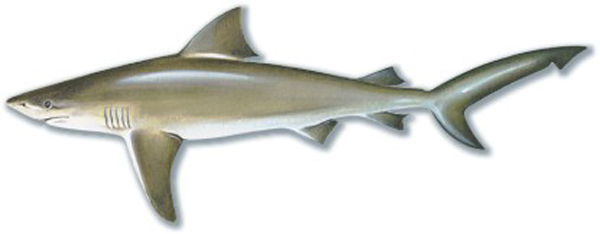

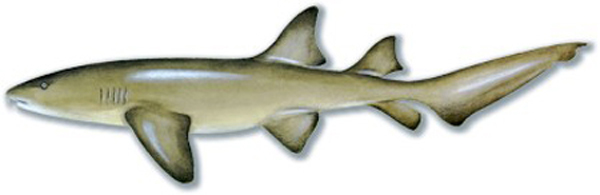

Atlantic Sharpnose Shark

Photo illustration by Diane Peebles

Scientific Name: Rhizoprionodon terranovae

Maximum size: 2-3 feet

Color: Grey, sometimes featuring brownish hues. Adults have white spots.

Diet: Small bony fish, crustaceans that live on the sea floor.

Body type: Small and stocky, often mistaken as a juvenile blacktip or spinner.

Conservation status: Low threat

Response to hook-and-line: Large stress response due to small size, relatively sensitive species. Best to limit fight time and release quickly, especially in the warmer summer months.

This abundant smaller shark can be found throughout Florida in most coastal habitats. Found commonly in bays, inlets, brackish areas, as well as offshore in deep water.

Bull Shark

Photo illustration by Dawn Witherington

Scientific Name: Carcharhinus leucas

Maximum size: 8-11 feet

Color: Dark grey and brown mix. Snout is broad and rounded.

Diet: Varied. Primarily fish eaters and will hunt other sharks.

Body type: Large and stocky, football shaped.

Conservation status: Moderate threat.

Response to hook-and-line: Moderate to high stress response. Species do not do well out of the water and may be prone to higher rates of hooking in areas other than the jaw. Best to use circle hooks and keep in water before release.

This species is a large apex predator which occupies the top of the food chain in almost every ecosystem. Notorious for their reputation and perceived (but not truly substantiated) risk to humans, bull sharks are relatively common throughout most of Florida. They are most abundant in bays and can inhabit both fresh and saltwater habitats. Bull sharks can also be encountered offshore during their migratory phases. The species seems to be starting to recover from decades of exploitation, but are by no means exploding in population size.

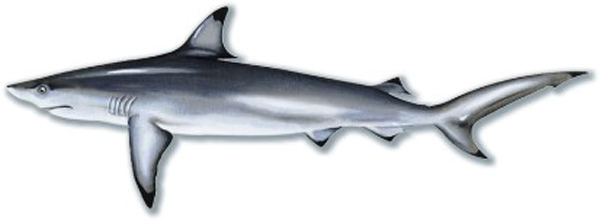

Blacktip Shark

Photo illustration by Diane Peebles

Scientific Name: Carcharhinus limbatus

Maximum size: 4-6 feet

Color: Brown and silver with occasional black streaks on sides. Bottoms of fins have black markings. Pointy snout. Unlike spinner sharks, blacktip skarks lack a black marking on the anal fin.

Diet: Varied. Primarily fish eaters.

Body type: Medium sized, pointy classic “shark” body.

Conservation status: Moderate threat.

Response to hook-and-line: Moderate to high stress response. Species will fight extremely hard for its size and can get exhausted quickly. Do not fight fish to exhaustion and release quickly.

This is a predominantly coastal species that is often found in groups, but can also be found offshore. Blacktip sharks are very energetic and fast, supporting the fact that they eat agile prey fish and must avoid being eaten by larger sharks. Individuals can sometimes be seen jumping out of the water when hooked or hunting prey.

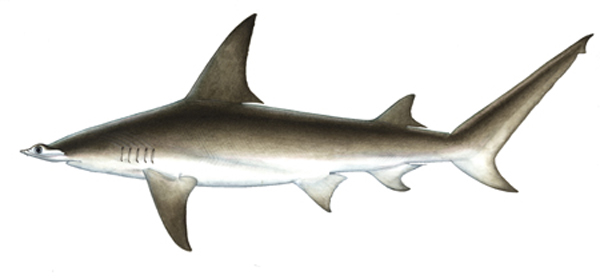

Hammerhead Shark (Great and Scalloped)

Illustration by Diane Peebles

Scientific Name: Sphyrna mokarran, Sphyrna lewini

Maximum size: 12-16 feet (Great), 8-11 feet (Scalloped)

Color: Grey and silver (Great), silver to golden (Scalloped)

Diet: Feed on fast-moving species, stingrays and other sharks.

Body type: Large, powerful bodies with distinctive hammer-shaped heads.

Conservation status: High threat.

Response to hook-and-line: Extreme. Very hard fighting fish that shows high mortality due to exhaustion in fisheries. If targeting, have a plan for release that includes bringing to boat swiftly. If cannot bring to boat, best to cut the line and let fish swim off and avoid further stress. Easily recognized by their distinctive hammer, these are large apex predators that can still be found in relative abundance throughout Florida. Hammerheads in general are a highly threatened species of sharks that must be treated carefully by anglers, even though they are a popular target species. Great hammerheads are the larger of the two species and have a much broader hammer, while the scalloped hammerhead is slightly smaller and has a curved hammer. These are protected from harvest in Florida state waters.

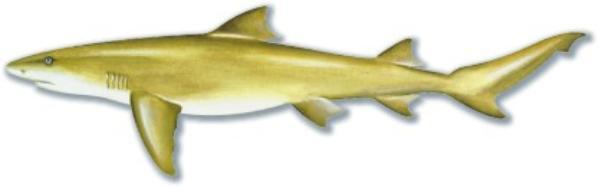

Lemon Shark

Illustration by Dawn Witherington

Scientific Name: Negaprion brevirostris

Maximum size: 6-8 feet

Color: Brownish with yellow hues.

Diet: Fish eaters.

Body type: Medium to large bodies with sickle-shaped fins. Lemon sharks have a second dorsal fin and have extremely pointy and sharp teeth that sometimes protrude from their mouths.

Conservation status: Moderate threat.

Response to hook-and-line: Low. This species does not get stressed from fishing and will show high survival with moderate catch-and-release fishing.

Lemon shark populations were once much greater than they are today in Florida, although they can still be found in a variety of habitats from bays to coastal ledges. These are protected from harvest in Florida state waters.

Nurse Shark

Illustration by Dawn Witherington

Scientific Name: Ginglymostoma cirratum

Maximum size: 5-7 feet

Color: Brown with sometimes orange or dark brown hues.

Diet: Small fishes and crustaceans that live on the sea floor.

Body type: Medium to large body. Nurse sharks are bottom-dwelling species and their body reflects this as being flat and low profile.

Conservation status: Low threat.

Response to hook-and-line: Low. This species does not get stressed from fishing and will show high survival with moderate catch-and-release fishing.

Nurse sharks are among the most common sharks in Florida. They are found in virtually all habitats and live on the bottom of the sea floor.

Tiger Shark

Illustration by Dawn Witherington

Scientific Name: Galeocerdo cuvier

Maximum size: 10-16 feet

Color: Silver body with white belly and black stripes which fade as they grow.

Diet: Fish, turtles, sharks, marine mammals and inorganic products. Very broad.

Body type: Very large apex predator.

Conservation status: Moderate threat.

Response to hook-and-line: Low. This species does not get stressed from fishing and will show high survival with moderate catch-and-release fishing.

Tiger sharks are easy to identify by their striped bodies. These sharks are apex predators in all ecosystems and prey on a wide range of food items. Tiger sharks are slowly recovering from decades of harvest in the Southeastern United States and are a great species for catch and release.

Additional Resources

- Shark Information (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Fish Handling Practices (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Common Sharks of Florida (Florida Sea Grant)

- A Guide to Circle Hooks (Florida Sea Grant)

- Recreational Shark Fishing Healthy Catch-and-Release (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Sustainable Sport Fishing for Thresher Sharks (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Podcast: Hooked on Sharks (NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Best Practice Shark Handling Guide (The Shark Trust)

- A Guide to Sharks, Tunas & Billfishes in the U.S. Atlantic & Gulf of Mexico (Rhode Island Sea Grant)

- Shark Biology and Conservation (MOTE Marine Laboratory)

- Sharks: The Animal Answer Guide (Gene Helfman and George H. Burgess)

- Circle hooks and sharks (Bulletin of Marine Science)

- Guy Harvey Research Institute Shark Tracker

Atlantic

Best Practices

Bring in the shark quickly. Longer fight times could mean the shark will be at a higher risk of mortality. (Prohibited or protected species that die while on the line after being caught must be returned to the water.) Use lots of drag and heavy enough tackle to limit extended fight times. Think about what size shark you will be catching. The bigger the shark, the heavier the tackle should be. Do not remove sharks from water – extended air exposure could be deadly. Take photos with the shark in the water.

Recommended Gear

- Circle hooks are generally recommended to promote jaw-hooking and avoid gut hooking most fish species. Some shark fishermen, however, believe that J-hooks may be more easily removed from sharks than circle hooks because circle hooks tend to get caught in a shark’s rough skin. Additional research is needed to determine the effectiveness of circle hooks for increasing shark survival in the recreational shark fishery.

What is known about the benefits of using circle hooks for shark fishing comes from research conducted in commercial longline fisheries, where shark capture occurs mostly as bycatch. Studies suggest that the use of circle hooks in the longline fishery does reduce at-vessel mortality compared to J-hooks, but more definitive research is needed before scientific consensus on circle hooks as a conservation tool for sharks can emerge.

- Bending barbs down is a good idea to make hook removal easier. Use non-stainless steel hooks so they can dissolve if they remain in the shark.

- Use a dehooking device to remove hooks safely. Longer handled tools work better for sharks.

- If a hook does not come out easily, use pliers to clip the leader as close to the shark as can be done safely.

- Do not gaff sharks you plan on releasing.

- Use a tail rope for species that are difficult to restrain.

- Use non-stainless steel hooks so they will rust out if they cannot be removed.

Additional Resources

- Shark Information(Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Fish Handling Practices(Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

- Common Sharks of Florida(Florida Sea Grant)

- A Guide to Circle Hooks(Florida Sea Grant)

- Recreational Shark Fishing Healthy Catch-and-Release(NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Sustainable Sport Fishing for Thresher Sharks(NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Podcast: Hooked on Sharks(NOAA Fisheries Service)

- Best Practice Shark Handling Guide (The Shark Trust)

- A Guide to Sharks, Tunas & Billfishes in the U.S. Atlantic & Gulf of Mexico (Rhode Island Sea Grant)

- Shark Biology and Conservation (MOTE Marine Laboratory)

- Sharks: The Animal Answer Guide (Gene Helfman and George H. Burgess)

- Circle hooks and sharks (Bulletin of Marine Science)

- Guy Harvey Research Institute Shark Tracker